Kangaroo Care: A Father's Story of Caring for His Premature Daughter

by John Anner | Published in Childbirth Instructor, Spring 1994

John's article on his experience with his first daughter being born prematurely was published in Childbirth Instructor.

When my wife Devora and I were allowed to go down the hall to the brightly lit intensive care ward, I did my best to pretend I felt something for this pitiful little creature, who was already hooked up to various monitors. As they beeped and whirred, their digital displays added to the feeling that I had taken a wrong turn somewhere and wound up in Mission Control. I tried to find a shadow of the joy and anticipation I had felt during the previous five or six months. Instead, I could summon up only anxiety and a cold sensation of being disconnected and out of control.

We sat with Eva all day that first day, Devora and I, looking at her in her plastic incubator. She didn't respond to talking, and we were told not to touch her too much for fear of overstimulating her undeveloped nervous system. We went home that night and cried—because we didn't have our baby with us, because of the unknown dangers ahead, but mostly because we had a child but couldn't seem to get close to her.

Within two weeks, however, we were holding Eva every day, all day long, sometimes as much as 10 or 12 hours a day, even though she had lost weight since being born and at three weeks was a miniscule 1 pound, 11 ounces. We were trying something that had never been done before in the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Intensive Care Nursery, a new "technology" that involves taking the preemie out of the incubator and putting her, naked, on her parents' chests, skin to skin. Called "kangeroo care," or "K-care" or "skin-to-skin" (the latter in those hospitals that don't want to give the impression they are experimenting with wacky gimmicks), the method originated in Colombia and has spread to hospitals in Europe and the United States.

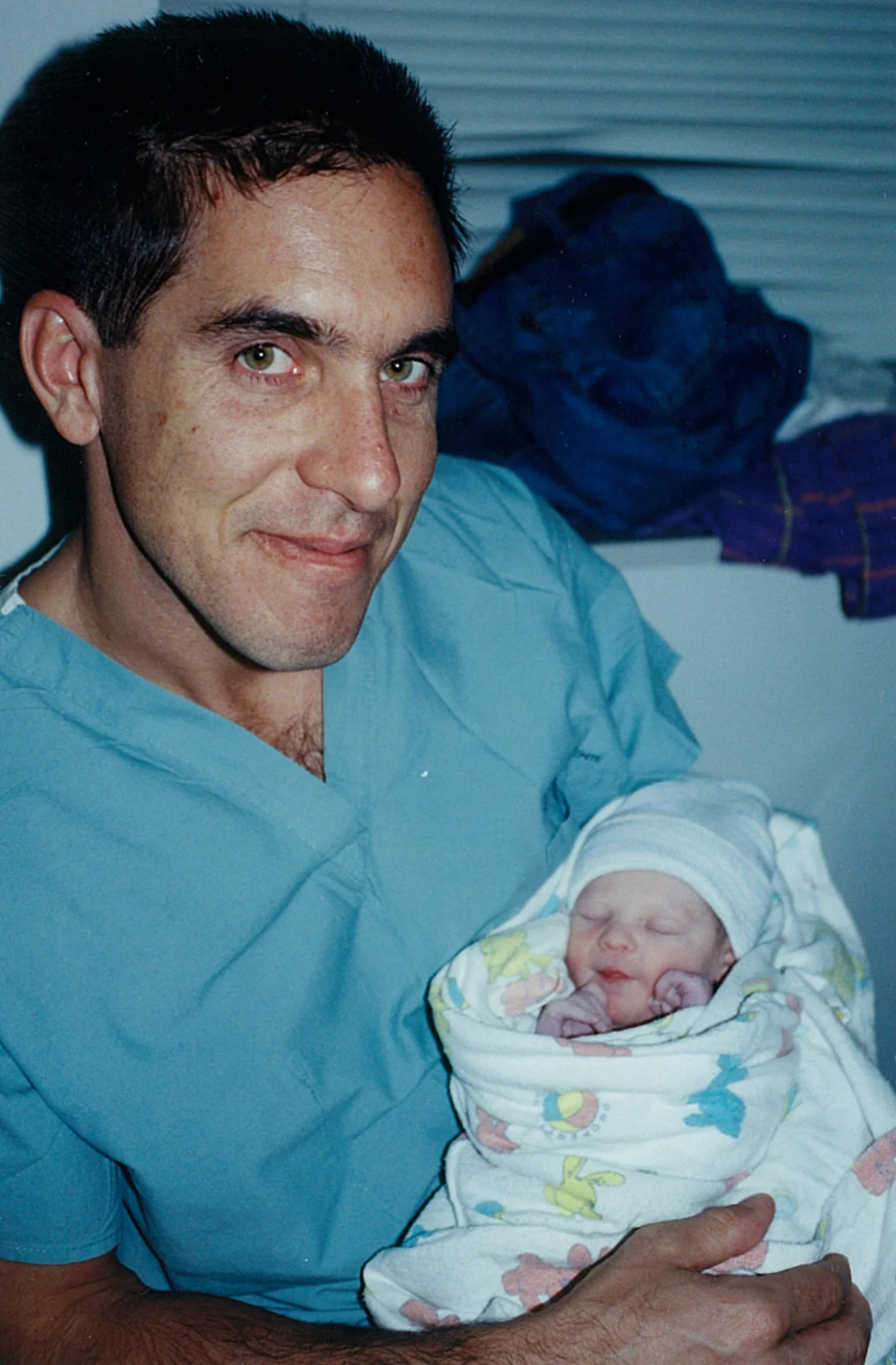

I held Eva against my chest about four hours a day for the first two months, with Devora getting her another four. I can't say for certain if it did Eva any good, although she was an unusually stable and healthy preemie and graduated from intensive nursery early. But for me, kangaroo care was the greatest thing that could have happened. Within five minutes during the first time I held her, I started to feel all those feelings of joy, tenderness, and love I thought I would never experience. I felt close to her. I felt like a father.

For me, kangaroo care was the greatest thing that could have happened. Within five minutes during the first time I held her, I started to feel all those feelings of joy, tenderness, and love I thought I would never experience. I felt close to her. I felt like a father.

Medical research suggests that my experiences and feelings before and after trying kangaroo care are typical. Parents of premature babies are often shocked and dismayed when they first see their new baby, stuck full of tubes and possibly wearing eye protectors while baking under the Bili-light. Hospital staff members frequently report hearing parents say things like "He doesn't look like a baby," and, "I don't feel like a mother." These feelings of helplessness and alienation are compounded by the fact the high-tech medical environment, by the endless litany of horrible things parents hear about what have gone or could go wrong with the baby, and by the sight of the plastic incubator box that should have been a warm crib.

Research conducted in Europe and the United States indicates that parents who use skin-to-skin care feel much more in control of the situation, and are more willing to question medical staff, spend more time in the nursery, and often can take their babies home earlier.

Anything that parents can do to feel like they are taking care of their infant helps. Even with the infant intubated and immobilized in the incubator, parents can change a diaper, take the axillary temperature, or rub on some skin moisturizer. The most rewarding activity, of course, is holding the baby. But for very low birthweight infants, temperature maintenance is a real problem, since they don't have much fat on their little bodies. The first few times we were allowed to hold Eva, wrapped in several blankets, we had to put her back in the incubator after no more than five or 10 minutes.

Kangaroo care solves this problem by having the parents provide the source of warmth. In the fact, the method was developed in 1979 by two Colombian physicians, Drs. Edgar Rey and Hector Martinez, who were faced with a shortage of incubators in their Bogota hospital. Incubators, however, do more than simply provide warmth. They also create a safe, stable, regulated environment that is designed to make it easy for doctors and nurses to administer care and to respond to emergencies. Rey and Martinez emphasized that they didn't advocate skin-to-skin for any and all preemies. Babies had to be stable before their parents could hold them.

On the other hand, parents provide more than just warmth, and the definition of "stability" varies from hospital to hospital. Douglas Henning, MD, a neonatal physician at UCSF and a strong advocate of skin-to-skin care, argues that "there may be some actual physiologic benefits that we haven't even looked at." He suggest, "It's possible there are [maternal] pheromones that stimulate certain reactions in the baby—I think there may be benefits that come from [the parent's] heartbeat, and from the motion of the parent's chest in breathing that help stop apnea and bradycardia. The babies might also benefit by being exposed to the family germs."

Maria Iorillo, a licensed lay midwife, points out that all babies need to feel loved and protected, especially ones who must live with frightening and painful medical procedures. "Midwives always encourage human skin contact," she says. "You can see how a baby relaxes when held close. Their stress level goes down."

Neonatologist Amarjit Sadhu, MD, at Children's Hospital in Oakland, California, said on the TV program Life Choices that he was initially skeptical of the procedure, but changed his mind after he saw the positive effects on parents and children. He said of close physical contact between parent and child, "Even if we don't understand it, it's something that is supposed to be there."

Most hospitals that allow parents to hold their preemies skin-to-skin have protocols that restrict, for example, the holding of babies who are below a certain weight, or who are intubated, or who are hooked up to other medical devices. Some hospitals are fairly conservative about what they consider "stable." Others such as Children's Hospital in Oakland, encourage parents to hold even intubated infants. In fact, in the medical literature on this subject, there don't seem to be any strict guidelines regarding restrictions. Whether a hospital allows and encourages skin-to-skin—and to what degree—appears to be more of a function of the culture of the medical institution.

Although skin-to-skin is now common in Europe, only about 80 hospitals in the United States currently support the practice. When asked why more neonatal intensive care units did not encourage patients to use kangaroo care, Henning replied, "Doctors are routinely suspicious of anything that is simple and straightforward. The idea that there is something that is absolutely natural that works is something that is resisted by the medical community, especially doctors." His colleague Linda Haller, RN, a head administrative nurse at UCSF, adds that by training and inclination, neonatal physicians are likely to believe more in technology than in intangibles. "ICN's tend to be infant-centered," she explains. "We realize that it is important to support the whole family, {and so} we are moving towards are more family-centered model." She sees kangaroo care as an integral part of this shift in focus, since it can play a role in bringing parent and child closer together.

There are many other obstacles to skin-to-skin becoming widely used in ICNs. Some parents are uncomfortable exposing their chests in the hospital; nurses might feel that it adds a burden to their workload and makes it difficult for them to administer care to the baby; or the ICN may have a higher proportion of severely ill or borderline babies. The more high-tech an ICN, and the higher the professional qualifications of the medical staff, the more likely it is that critically ill and very low birthweight babies will be patients. Many of these babies are not good candidates for kangaroo care.

However, says ICN nurse Hana Protopapa, "I actually believe that this is not a clinical issue. The clinical pros and cons are small, compared to the humanistic issues involved. So the clinical issues should basically be kept out of it, but that doesn't work in a system like ours." She says that once the basic medical conditions are met, the question of whether skin-to-skin will be encouraged and used is really up to the nursing staff, since "they are on the front lines." What this means is that if the nurses are comfortable telling parents about kangeroo care and helping them do it, and "if they are okay about having half-naked people" in the nursery, a lot of the clinical issues are left to the nurse's discretion.

"The only way for nurses to get comfortable with the practice is to see parents doing it," says Haller, who has played a key role in introducing skin-to-skin at UCSF (where it emphatically is not called "kangaroo care"). Haller's research indicates that it is best to introduce the practice slowly, and gradually move toward a more relaxed protocol as the nurses become familiar with it. The UCSF protocol on skin-to-skin requires that the baby weigh at least 1,200 grams, not to be intubated, have fewer than six episodes of apnea and bradycardia per day, and have no other arterial lines or chest tubes (a stable I.V. is acceptable).

Protopapa was the first nurse to help us do skin-to-skin, after we asked to try it. She had heard about it but had never seen it done. (None of the doctors and nurses I spoke with had ever seen a man do it although it is apparently common in Europe and Colombia.) After seeing us do it, several other parents asked to try it. However, when I dropped in the other day to say hello and show off Eva, none of the 30-odd babies in the ICN were being held skin-to-skin. "What's really going to change things," says Haller, "is when parents hear about it and start demanding to do it."

So why should a childbirth educator get to know about kangaroo care? It could make all the difference for a client who has just suffered the tremendous shock of an unexpected premature birth. This is especially true when the practice is not know of or encouraged in the hospital where the new family winds up—a situation that is more likely in the United States. Now, based in part on our experience, UCSF has a policy on skin-to-skin care. There's even a poster in the parents' lounge that includes a photo of Devora holding Eva.

Devora and I had planned a home birth. Our discussions had to with what kind of music to play and how to keep the rug from getting messed up. We had never heard of an intensive care nursery, never mind the jargon so common there—CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), patent ductus arteriosis (a heart anamoly common in premature infants), OG (orogastric tubes). We found out about skin-to-skin from our midwife, who bolstered us to insist that we be allowed to do it.

And we are glad we did. Eva is now a perfectly normal baby in every way. However, Devora and I feel that we have some unfinished business with kangaroo care. We are planning a trip to Australia to find out how the kangaroo moms keep their babies from getting up at 4:00 in the morning!

Read John's more recent and updated article on his daughter's premature birth as well as advancing technology to help reduce neonatal mortality, published in Healthy Newborn Network.